YINCHUAN, China — The praying and slaughtering begin every morning at sunrise. “Allahu Akbar” intones the imam over each cow before it is strung up by its hooves and quartered.

This scene, and other religious and ethnic practices, set China’s Muslim minorities apart, and the differences frequently led to clashes with the Chinese government in the past. But the country’s leaders are now embracing the large Muslim population in this remote and relatively undeveloped city in the western province of Ningxia, hoping that frozen packs of halal meat produced here can help build economic bridges with the Middle East.

This scene, and other religious and ethnic practices, set China’s Muslim minorities apart, and the differences frequently led to clashes with the Chinese government in the past. But the country’s leaders are now embracing the large Muslim population in this remote and relatively undeveloped city in the western province of Ningxia, hoping that frozen packs of halal meat produced here can help build economic bridges with the Middle East.

With U.S. and European markets still recovering, the Arab world is an increasingly enticing market for Chinese exports and a potential source of investors for Chinese projects. Middle Eastern countries are also some of the closest positioned to help develop China’s western provinces, which have fallen far behind its flourishing eastern coastal cities during the past three decades of economic boom.

Perhaps most important, on a strategic level, China wants to protect and strengthen its access to the region’s oil and energy resources, which are fueling the country’s economic growth.

“The short-term goal of increasing halal meat going to Arab countries is to build up our local economy and workforce,” said one provincial official here, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss the strategy of central authorities above his rank. “But the real goal is to introduce the Arab world to us and get them comfortable with the idea of building up their relations and investment in China. .?.?. And energy is not the only reason behind it, but it is a big one.”

China’s government has thrown considerable diplomatic and political resources into building up Middle East ties during the past five years. Lavish conferences have been sponsored across the country, ethnic festivals held to celebrate Chinese Muslims’ heritage, and trade delegations sent out from both sides, including two visits to Saudi Arabia by outgoing Chinese President Hu Jintao.

The most recent large-scale event — an economic forum that included high-level dignitaries from China and the United Arab Emirates — took place this fall in Yinchuan, the capital of Ningxia province. In private conversations on the sidelines, Chinese officials described an overall strategy to reach out to the Middle East that was laid out in broad terms by central authorities, then planned and executed in more detail by local officials.

So far, the efforts appear to have produced some positive results. Last year, Sino-Arab trade increased by 35 percent to $196 billion, according to Chinese officials, and in the first half of this year trade rose 22 percent over the same period in 2011, to $111.8 billion. The trade remains dominated by oil, but Chinese exports such as textiles and home appliances have made a strong showing, according to limited data released by Chinese officials.

Ambitious plans

The decision by central authorities to make Ningxia a focal point for bridge-building efforts to the Middle East gave local business leaders a much-needed boost of hope.

It is hard to find a province more in need of development. A dry desert land largely left behind during China’s economic boom, Ningxia has the country’s third-smallest gross domestic product and few exports it can rely on besides a fruit called wolfberry.

One thing it does have in abundance, however, are Muslims. Two million members of the predominantly Muslim ethnic minority called Hui live here, making up a third of the province’s population. The Hui are believed to be descendants of Arab and Persian traders stemming back to the ancient days of the Silk Road.

One thing it does have in abundance, however, are Muslims. Two million members of the predominantly Muslim ethnic minority called Hui live here, making up a third of the province’s population. The Hui are believed to be descendants of Arab and Persian traders stemming back to the ancient days of the Silk Road.

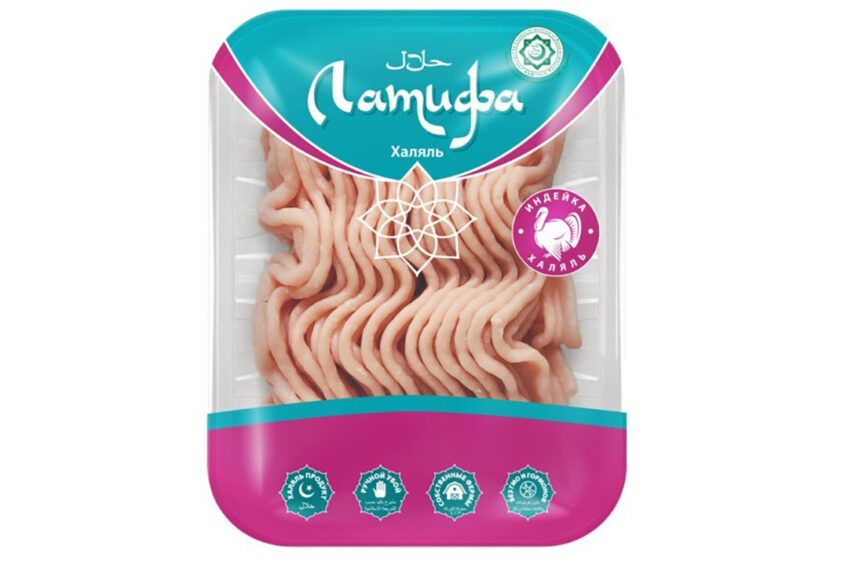

For now, local officials plan to start small, hoping to export such products as halal meat. But there are ambitious — and perhaps overly optimistic — plans to eventually turn the province into a gleaming financial hub for trade with the Arab world.

At the Yinshun company’s slaughterhouse and meat factory on the outskirts of town, Vice General Manager Yang Li, an ethnic Hui, described the company’s goals as largely profit-driven but also patriotic and cultural.

Almost half the staff are Hui, and the company follows strict Islamic rules about what their cows and sheep eat and drink, when slaughter can occur and under what conditions.

The factory, only two years old, has already hosted high-level dignitaries from Muslim countries including the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia.

But there have been some obstacles to increasing its exports, chief among them getting its halal meat certified under byzantine and often protective national laws of many Arab states. The Yinshun company, for instance, shipped 125 tons of halal meat last year to countries in the Middle East, but it is now in pursuit of deals that could increase that figure more than 10 times over, officials said.

A profit-oriented approach

While Chinese officials have talked about their hope to diversify trade with the region, the lion’s share of Sino-Arab trade still consists of oil. Similarly, the long-term goal of luring investors from the Middle East has been slow to materialize, several officials from both sides acknowledged.

“It’s true there’s still not much investment coming from Arabic countries,” said Nazha Aschenbrenner, director of a trade initiative created by the UAE’s ministry of foreign trade. Highlighting the shared Muslim culture and religion in places such as Ningxia province helps, she said. But ultimately, business decisions always come down to money.

Potential Chinese partners “have to keep in mind two factors: efficiency and marketing. Then investors will see that there is potential for profit,” she said. “In the end, investment isn’t colored by religion, it is profit-oriented.”