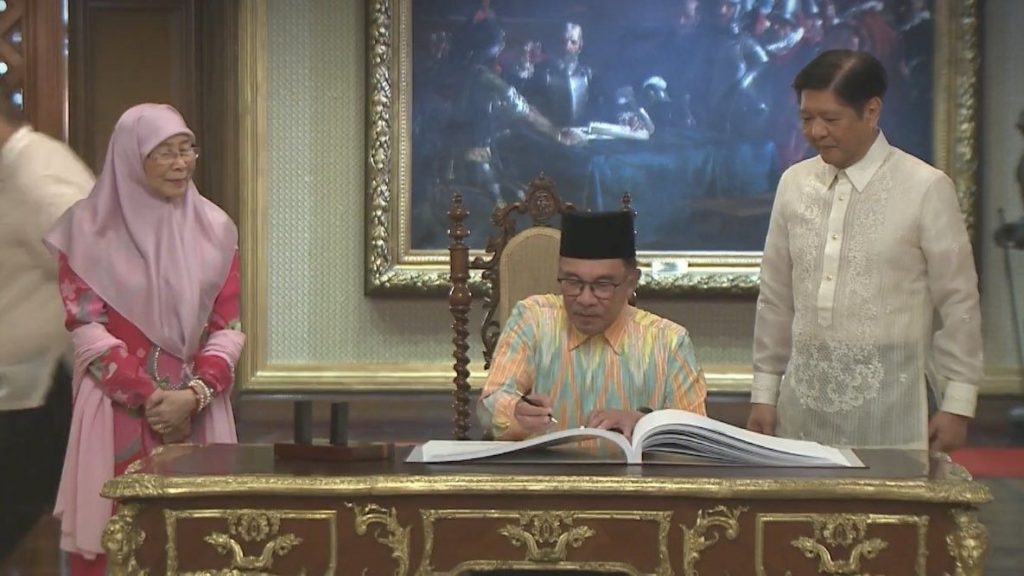

THE Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement entered into force for Malaysia on March 18.

THE Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement entered into force for Malaysia on March 18.

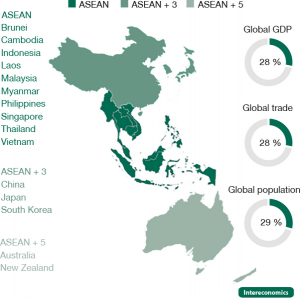

It is a treaty between 15 countries: Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

It is also the largest free trade group of countries.

Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) is an international treaty between Japan and another country that gives commitment to eliminating or reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers on exports and imports of goods as well as regulations on service sectors.

It also improves investment environments and enhance protection of intellectual property. EPA covers a scope of economic partnership in facilitating free movement of goods, services, capital, technology and people. All are part and parcel of economic integration between two signatory countries.

“Comprehensive” refers to the difference in development level between Japan and a group of signatory countries. Hence, the RCEP agreement provides assurance of strong commitment to development cooperation between member countries.

There are about 2.27 billion inhabitants in the RCEP region. Their gross domestic product (GDP) was about US$26 trillion in 2020, about one third of world GDP. Total value of exports was US$5.42 trillion in 2020, or about 31 per cent of world exports.

More excitingly, this group of countries is expected to record an average economic growth of five per cent per annum in the next 10 years. This means the group’s GDP will become US$42.35 trillion in 2032.

After that, the annual growth rate will likely hover at about two to three per cent.

Put differently, I expect the RCEP will grow by between US$850 and US$1,270 billion a year after 2032. This is about 2.4 to 3.5 times of Malaysia’s GDP last year.

That said, I must underline three important elements:

• Sustainability of renewal and non-renewal natural resources; Global warming and climate change; Healthy lifestyles in a post-Covid-19 pandemic world;

• Individuals, businesses and government can mutually enhance sustainability and healthy lifestyles in every community. Every agent must support Sustainable Development Goals and Corporate Social Responsibility;

• Responsibility and Environmental, Social and Governance. The task is not easy but certainly doable. I have written about these issues last year.

We know that Malaysia is a top exporter of rubber, palm oil, as well as electrical and electronics products. While they will remain important earners in the future, we would need to strengthen the labour productivity as much as the technological capability.

The focus on low wage labour-intensive manufacturing will no longer add values to our economy. Whereas the RCEP will not only provide the ladder to lift our labour productivity, it also is the new avenue for creating higher value-added goods and services.

I believe that many will echo my view.

Just as important, if not more, I want to reiterate the significance of the Islamic economy. It will give added tangible and non-tangible benefits to RCEP member states.

RCEP’s per capita income in 2020 was about US$11,100. Intra-regional trade value grew from US$2.03 trillion in 2010 to US$2.51 trillion in 2020 (two per cent annual growth).

Moreover, I can add two more assumptions: the size of private final consumption per annum is 60 per cent on average while it’s about 25 per cent for annual investments.

The former represents the value between US$15.6 and US$25.4 trillion in 2022 to 2032. The latter is about US$6.5 to US$10.6 trillion. Hence, the size of population, GDP, investments and trade is incredibly huge.

The frontier for expanding supply and demand is huge. Markets will undoubtedly expand for intermediate goods, durable and non-durable consumer goods, medical and healthcare, services such as food and beverages, retailing, finance and banking, and so on.

In this regard, the Islamic economy can bring added tangible and non-tangible benefits to member states in the RCEP. It is a crucial platform for promoting trade and investments in halal business in and outside Malaysia.

My colleague and I have analysed 27 sectors that are of relevance to the halal economy. The selection is based on goods or merchandises and services that are essential to a healthy lifestyle post-pandemic.

Each is consistent with the Malaysia Standard Industrial Classification 2008. Although we have explained our findings in earlier column, I want to reiterate the key takeaways.

Our analysis confirms that Malaysia is strong in production, consumption and export of halal products and related goods/services. Moreover, that strength can be further optimised through directed domestic and foreign investments leveraging Malaysia’s Gold Standard Halal certification.

The imperative of foreign inward investments in halal sectors is particularly significant because of the large volume of domestic production it induces. The inducement effects for compensation are also impressive in terms of bigger domestic demand and more foreign inward investments for producing halal goods and services, not to mention increased employment.

We found that domestic demand and exports indeed mutually reinforce foreign inward investments in the halal sector. Imports also equally induce increased domestic production in the domestic and international marketplace.

Hence, the International Trade and Industry Ministry and HDC Bhd must incentivise the production of halal goods and services to expand and solidify their marketplaces in and outside Malaysia.

Their interventions through the RCEP are the clear and present opportunity that will continuously lift our living standards founded on sustainability.

Just as important, both institutions can make small and medium companies — income and employment generators — drive the growth of halal business in the RCEP, too.

The writer is a professor at Reitaku University, Tokyo, and has been teaching Southeast Asian studies, international economics, integration, development economics and Asian economy since 1983