By selling modest clothing or spotlighting a hijabi in an ad campaign, the U.S. clothing industry is beckoning Muslim women to be its latest consumer niche. In order to tap into the multibillion-dollar potential of the U.S. Muslim consumer market, large retailers have positioned themselves as socially conscious havens for Muslims, operating on a profit motive rather than a moral imperative.

Many Muslim women, especially those who grew up post-9/11, may find inclusion as consumers to be a reprieve from everyday Islamophobia. However, the representations circulated by retail companies are reductive of Muslim-American identity. Certain Muslim women who conform to expectations of patriotism and consumption are granted visibility, while others, like black Muslim women, are erased from the narrative of Islam in America. Meanwhile, Muslims whose labor is exploited overseas are disappeared from corporate conscience.

For full original article go to:

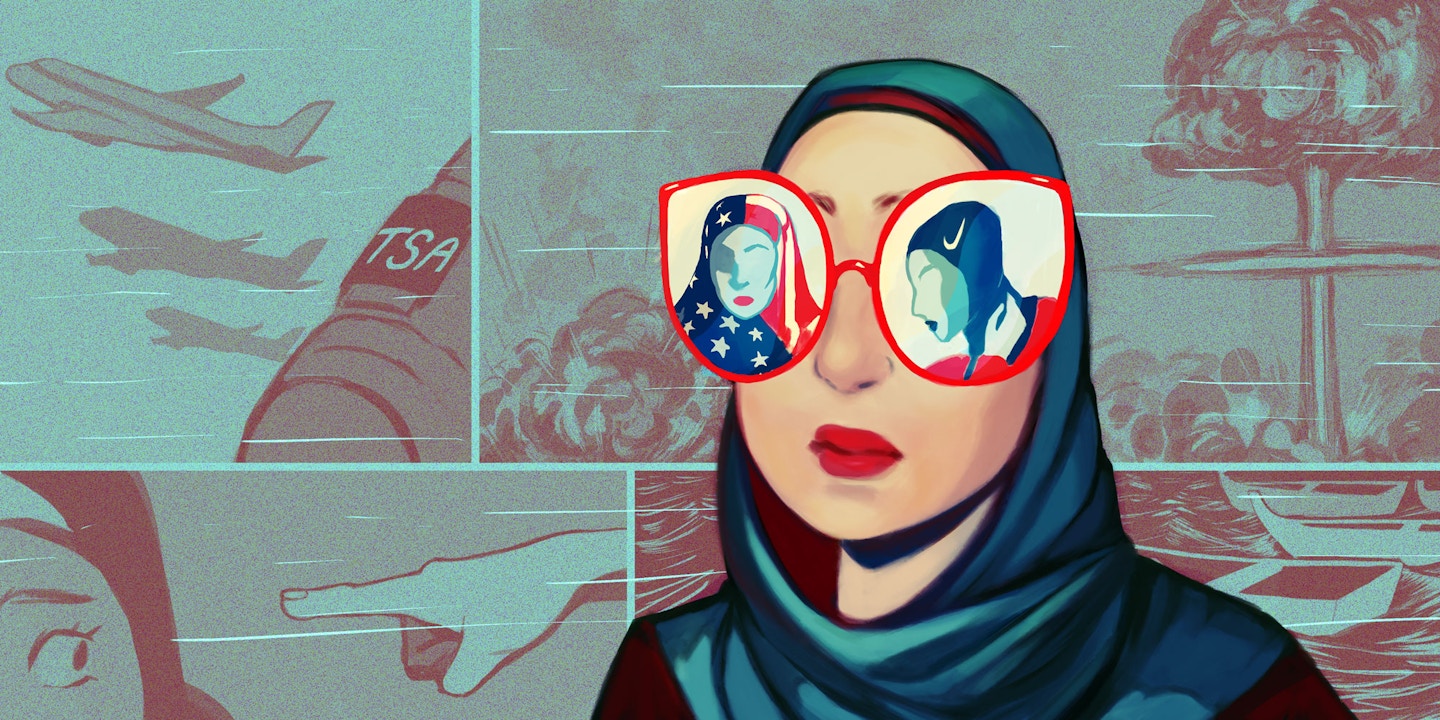

Nike released its first sports hijab last December, heralded with sleek, black-and-white photographs of accomplished Muslim athletes wearing the Pro Hijab emblazoned with the iconic swoosh. The same month, TSA pulled 14 women who wear hijab out of a security check line at Newark Airport; they were then patted down, searched, and detained for two hours.

From February to March, Gucci, Versace, and other luxury brands at autumn/winter fashion week dressed mostly white models in hijab-like headscarves. Around that time, two women filed a civil rights lawsuit against New York City related to an incident in which the NYPD forced them to remove their hijabs for mugshots.

Gap, a clothing brand known for its all-American ethos, featured a young girl in a hijab smiling broadly in its back-to-school ads this past summer. Meanwhile, children were forced to leave a public pool in Delaware; they were told that their hijabs could clog the filtration system.

Muslim women and Muslim fashion currently have unprecedented visibility in American consumer culture. Yet women who cover are among the most visible targets for curtailed civil liberties, violence, and discrimination in the anti-Muslim climate intensified by Donald Trump’s presidency.

By selling modest clothing or spotlighting a hijabi in an ad campaign, the U.S. clothing industry is beckoning Muslim women to be its latest consumer niche. In order to tap into the multibillion-dollar potential of the U.S. Muslim consumer market, large retailers have positioned themselves as socially conscious havens for Muslims, operating on a profit motive rather than a moral imperative.

Many Muslim women, especially those who grew up post-9/11, may find inclusion as consumers to be a reprieve from everyday Islamophobia. However, the representations circulated by retail companies are reductive of Muslim-American identity. Certain Muslim women who conform to expectations of patriotism and consumption are granted visibility, while others, like black Muslim women, are erased from the narrative of Islam in America. Meanwhile, Muslims whose labor is exploited overseas are disappeared from corporate conscience.

The Muslim Consumer Market

In February, Macy’s became the first U.S. department store to sell a modest clothing line, called the Verona Collection. Macy’s was widely praised as “inclusive” and “taking diversity very seriously.” Refinery29 raved, “It’s great to see Macy’s really taking the steps to champion the causes it says it believes in.”

Macy’s debuted the Verona Collection shortly after the retailer announced that several stores would close in 2018 (more than 120 stores have shuttered since 2015). A week before the launch, Macy’s stock hit its lowest point of 2018. But soon after the announcement, things seemed to be looking up for the flailing company. A business analyst said, “At this time for investors the new clothing line should be treated with cautious excitement for what it may mean for the company moving forward.”

Macy’s financial instability when starting to sell hijabs and modest clothing calls into question the motive behind suddenly catering to Muslim consumers. Why now?

“It feels like a way of generating publicity by putting out an inclusive image, trying to make themselves seem more relevant,” Sylvia Chan-Malik, author of “Being Muslim: A Cultural History of Women of Color in American Islam,” told The Intercept. “But perhaps that’s cynical, because I know a lot of Muslim women who were very happy about it. I just don’t know what the intentions are.”

In addition to Nike, Gap, and high-end designers, there are several recent examples of the U.S. retail and fashion industry courting Muslim women who dress modestly. In 2016, New York Fashion Week presented its first all-hijab runway show from Indonesian designer Anniesa Hasibuan. That November, CoverGirl brought on hijabi beauty blogger Nura Afia as its latest brand ambassador. This past May, H&M released a modest clothing line leading up to Ramadan.

Since the early 2010s, multinational Western companies have catered to Muslim consumers after marketing consultants identified them as an influential demographic with growing spending power. According to the latest Thomson Reuters State of the Global Islamic Economy Report, Muslims worldwide spent about $254 billion on clothing in 2016, which was predicted to increase to $373 billion by 2022.

Western retailers have mostly concentrated their Muslim outreach to foreign consumers. Dolce & Gabbana, Tommy Hilfiger, and DKNY are among the brands that have sold Ramadan capsule collections or stocked modest clothing exclusively in their Middle East outlets. This past summer, MAC Cosmetics put out a glamorous makeup tutorial for suhoor, the pre-dawn meal during Ramadan, targeted at women in the Gulf region.

Consumer research on the U.S. market revealed a similar opportunity for profit. In 2013, Ogilvy Noor, the “Islamic branding” division of advertising company Ogilvy, estimated American Muslim spending power to be at $170 billion. DinarStandard and the American Muslim Consumer Consortium reported that Muslim-Americans spent $5.4 billion on apparel that same year.

Ogilvy Noor has determined that Muslim millennials are driving consumption with their collective belief that “faith and modernity go hand in hand.”

“If I was to pick one person who represents the cutting edge of Muslim futurists, it would be a woman: educated, tech-savvy, worldly, intent on defining her own future, brand loyal and conscious that her consumption says something important about who she is and how she chooses to live her life,” explained Shelina Janmohamed, vice president of Ogilvy Noor, who is Muslim. “The consumers these brands are targeting are young, cool and ready to spend their money.”

Ogilvy Noor’s approach inches toward essentializing who young Muslims are, which can then be monetized by corporations. The staggering economic power of the Muslim market is the determining factor in retail efforts to tap into it — less so a response to what Muslims could actually benefit from. But for many young Muslim women, consumer visibility can signal mainstream recognition and belonging, regardless of corporate intention.

“Maybe I’ll Feel More Safe”

While retailers are ultimately incentivized by profit, clothing and cosmetics brands are also providing more options for women who choose to cover, as well as fulfilling some hijabis’ desires for representation, said Elizabeth Bucar, author of “Pious Fashion: How Muslim Women Dress.”

“Muslims are a large part of the American population today — they’re visible,” Bucar, an associate professor at Northeastern University, told The Intercept. “They’re running for office, they’re our co-workers, they’re our neighbors, and, from a retail point of view, they are also consumers.”

Many Muslim women celebrate, and actively participate in, efforts to acknowledge them as consumers. Muslim beauty and fashion bloggers on Instagram and YouTube promote brands to hundreds of thousands of followers. Verona Collection designer Lisa Vogl and model Mariah Idrissi are among those who have found commercial success in collaboration with large brands.

In September, the de Young Museum in San Francisco opened the first major museum exhibition on contemporary Muslim fashions, signaling that Muslim women’s clothing is a legitimate topic of interest in the U.S. “We wanted to share what we’ve been seeing in Muslim fashion with the larger world in a way that could create a deeper understanding,” the de Young’s former director, Max Hollein, told the New York Times.

Consumer visibility can also signal a step toward the inclusion of Muslims as American in politically hostile times, particularly for the generation who grew up during the war on terror, when most representations have cast Muslims as foreign terrorists and a threat to national security.

“It’s incredibly validating on an individual level to Muslim women who wear the scarf, who have to struggle with the comments and the vitriol and the violence that they encounter every day,” said Chan-Malik, an associate professor at Rutgers University. “It’s almost a very practical sense of relief, like, ‘Oh, if this becomes more normalized, maybe I’ll feel more safe.’”

That increased representation is meaningful to some Muslim women cannot be ignored. However, who gets to be seen and how exposes the underlying logics of capitalism that flatten visibility into which Muslim women are the most marketable.

The “Hijab Fetish”

The market homogenizes Muslim women, collapsing tremendous diversity into a product that can be easily digested. “Certain kinds of representation and visibility are privileged, while others are rendered undesirable,” write Duke University associate professor Ellen McLarney and University of North Carolina associate professor Banu Gökariksel. “Muslim identities unpalatable to the sensibilities of the market are excluded, often leading to further marginalizations at the intersections of class, race, and ethnicity.”

This is evident in how the fashion and beauty industries grant visibility to certain Muslim women. Writing about the “hijab fetish” in consumer culture, Guardian columnist Nesrine Malik described how representations of Muslim women in advertising conform to “an image of an over-filtered, hot, bourgeois, fair-skinned hijabi woman, whose highlight is ‘on fleek’.”

In fact, most Muslim women in the U.S. do not always wear a headscarf in public; one-fifth of American Muslims are black; almost half of Muslim-Americans reported incomes under $30,000 last year; and many American Muslims identify as queer, transgender, and gender nonconforming.

Despite the fact that black Muslim women are largely absent from mainstream consumer culture, said Kayla Wheeler, an assistant professor at Grand Valley State University, the women of the Nation of Islam and the Moorish Science Temple laid the foundation for Muslim fashion in the U.S decades ago.

“The Nation of Islam tried to use clothing to give black women a new respectable identity that they had been denied by white supremacy, so they could … push back against stereotypes of black women as promiscuous or asexual or not real women or humans at all,” said Wheeler, who researches black Muslim women’s fashion.

Somali-American model Halima Aden and Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, along with designers Nzinga Knight, Eman Idil, and Lubna Muhammad, are among the few black Muslim women who have been given visibility in the fashion industry.

Black Muslim women are triply vulnerable in the U.S. to racist, misogynistic, and Islamophobic attacks.

Wheeler said that black Muslim women’s headscarves can be racially distinctive in wrapping styles and fabrics — nuances that are obscured among the commercial images of predominantly Middle Eastern and South Asian women. Meanwhile, black Muslim women are triply vulnerable in the U.S. to racist, misogynistic, and Islamophobic attacks (last month, a white man pulled a gun on a group of black Muslim teenagers, including headscarf-wearing girls, at a McDonald’s in Minnesota).

“Black Muslims are not seen as sympathetically as brown Muslims,” Wheeler told The Intercept. “Everyone faces Islamophobia, but when you add anti-blackness and suspicions about black Islam not being real Islam, they become not only a foreign threat, but a domestic threat.”

Corporate posturing to marginalized groups — what University of Denver law professor Nancy Leong describes as racial capitalism — has long been a business practice to persuade minority groups to become brand loyal and liberal consumers to buy products as a political statement.

In January, L’Oréal Paris announced its “unique and disruptive” hair care ad campaign, featuring model and social media influencer Amena Khan. In the ad, she wore a pale pink hijab, with a pink blazer, in front of a pink background. Within a week, Khan left the campaign after her tweets criticizing Israel for its attack on Gaza in 2014 were surfaced. In a statement, L’Oréal Paris agreed with her decision to step down, saying that the company is “committed to tolerance and respect towards all people.”

Brands “want the face, but they don’t want the complex politics or the identity or the voice behind it,” Hoda Katebi, a political fashion blogger and community organizer, told The Intercept, pointing to her own experiences with brands that have approached her to collaborate or model their clothing. “Once a Muslim woman asserts her agency, they’ll strip that away.”

The fetishization of the hijab descends from decades of stereotypical images that have been used to fortify imperial projects in the Middle East and Islamophobic policies and attitudes at home. U.S. meddling in Muslim-majority countries and the war on terror have been the political backdrops against which retailers and advertisers have commodified Muslim women and their clothing.

The Veil and U.S. Empire

The representation of Muslim women and the veil in U.S. consumer culture has historically shifted alongside the agenda of U.S. empire. The veil, which encompasses myriad forms of head covering, has been attributed multiple, often contradictory, meanings: empowering, oppressive, threatening, fashionable, subversive.

For decades, the myth of imperial benevolence has informed U.S. foreign policy, alongside feigned concern about Muslim women and their material conditions, which has advanced agendas that benefit the political and economic elite.

The veil became fetishized in the U.S. during the Iranian women’s movement after the 1979 revolution, Chan-Malik told The Intercept. Women mobilized for a week of protests after Ayatollah Khomeini, who replaced the U.S.-backed Shah Reza Pahlavi, established compulsory veiling, rather than allowing women to choose whether to cover.

The U.S. media focused on the chador as the symbol of oppression that the “poor Muslim woman” was forced to suffer under the ayatollah’s rule, Chan-Malik writes in her book. “Women’s rights became a rallying call that could be employed by the United States to explain the ills of the Middle East and the ‘terror’ of Islam.”

The images produced and circulated during this time established an American Orientalism that continues to inform ideas about Muslim women as oppressed and in need of a U.S. savior.

In her book “The Veil Unveiled: The Hijab in Modern Culture,” University of Texas at Austin professor Faegheh Shirazi lists pre-9/11 marketing strategies based on Orientalist stereotypes, which were used to sell cars, computers, perfume, and even soup: “the mysterious woman hiding behind her veil, waiting to be conquered by an American man; the submissive woman, forced to hide behind the veil; and the generic veiled woman, representing all peoples and cultures of the Middle East.”

In the wake of 9/11, the burqa became the most visible symbol of the Afghanistan War, weaponized to serve the Bush administration’s imperial agenda. In her infamous radio address, first lady Laura Bush claimed that the Taliban would “threaten to pull out women’s fingernails for wearing nail polish,” a harrowing detail suggesting that even beauty products were subject to tyrannical policing. The unveiling of Afghan women would come to represent their “freedom,” as well as their transformation into consumers.

After the Taliban fell, the U.S. beauty industry acted as an arm of empire and seized the opportunity to export Western products and techniques to Afghanistan. Marie Claire and Vogue magazines, joined by beauty companies like Paul Mitchell and Estée Lauder, funded the humanitarian-inflected “Beauty Without Borders,” a beauty school in Kabul meant to teach women how to perform salon services, despite the fact that salons had already existed. American shampoo and makeup became tools to liberate Muslim women.

By the early 2010s, the veil was still viewed with suspicion when worn by Muslim women, but had otherwise become an edgy, often sexualized, commodity. “Burqa chic” in fashion magazines and runway shows played upon the veil’s shock value, McLarney writes. Jeans brand Diesel released an ad in 2013 featuring a topless, tattooed white woman wearing a niqab, and non-Muslim celebrities, including Rihanna, Madonna, and Lady Gaga, toyed with wearing veils as if they were costumes. Capitalist manipulation, McLarney writes, had transformed the veil “from emblem of utter dehumanization to expression of fashion, protest, and even personal freedom.”

Muslim women’s clothing has acquired new significance under the Trump administration, which tacitly endorses the exclusion, hatred, and criminalization of Muslims. Trump’s call for a Muslim registry and a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” on the campaign trail, which manifested as the de facto Muslim travel ban, set the tone for his approach to U.S. Muslims.

In response, liberals have turned the Muslim woman into a feminist icon. The stylized image of a woman wearing an American flag as a hijab, created by street artist Shepard Fairey, hovered above crowds at the Women’s March as a symbol of multicultural inclusion and political resistance. However, as many have pointed out, the image distorts the history of state violence and injustice against Muslims in the U.S. and abroad — and the American feminist movement’s complicity in that. The poster’s conspicuous presence at anti-Trump demonstrations also invoked how Muslim-Americans are rendered visible in ways that can be harmful to the community.

The Politics of Visibility

The selective visibility of hijabis reinforces a false binary between “good” and “bad” Muslims, upholding liberal, flag-waving Muslims as tolerable and benign without rectifying deeply entrenched perceptions of Muslims as terroristic and fanatical. While most Americans do not personally know a Muslim, Pew Research Center reported that Muslims are regarded with the most negativity among religious groups. A recent study also found that terror attacks with an alleged Muslim suspect receive 357 percent more media coverage.

“People love good, patriotic Muslims who don’t threaten whiteness, who don’t challenge the historical and systematic violence that this country is built upon,” said Aqdas Aftab, who wrote about the hijab and capitalism as a fellow for Bitch Media.

As Muslim women are increasingly embraced in consumer culture, Nazia Kazi, author of the book “Islamophobia, Race, and Global Politics,” said that Muslim men are still regarded as “sexually frustrated, violent, inherently patriarchal figures” — stereotypes that materialize in the ongoing criminalization of Muslim men.

Muslims in the U.S. have been monitored via state-sponsored policing and surveillance, Kazi writes in her book, as well as through “everyday curiosity, concern, and watchfulness.” When it comes to Muslim women, she writes, observation turns into “voyeuristic fascination.”

“Muslim women, specifically those who wear hijab, are a unique source of curiosity and sympathy and bigotry and Islamophobic assumption,” Kazi, an assistant professor at Stockton University, told The Intercept.

That bigotry has increased in the Trump era, when flagrant Islamophobic rhetoric and policies have coincided with a reported increase in discrimination and abuse against Muslims. The Council on American-Islamic Relations reported a 17 percent increase in anti-Muslim bias incidents from 2016 to 2017, a trend that continued into 2018. This year alone, there have been numerous reports of hijabis being harassed, verbally abused, pushed in the subway, and assaulted by having their hijabs pulled off.

Kazi called the approach that retail companies have largely taken to address Islamophobia “leveraging hypervisibility,” or harnessing the heightened scrutiny of Muslims to highlight the most exemplary. That has the effect of rendering invisible “just how devastating Islamophobia is for the most marginalized among Muslim women around the world,” she said.

The clothing industry, for example, magnifies visibility of certain Muslim women, while hiding others from public view — those whose labor is exploited in garment factories overseas.

The global production of fast fashion depends on sweatshop labor to bring the latest runway trends to clothing racks. Gap and H&M use factories in Muslim-majority countries that have been accused of gender-based violence and labor abuses. Nike, notorious for its decadeslong dependence on sweatshop labor, also uses factories in predominantly Muslim countries.

“Who will hold them accountable for underpaying, overworking, and harassing their vulnerable employees when the same companies are being lauded for being inclusive and liberal?” Aftab said.

Muslims who applaud the commercialization of the hijab should be cognizant of the exploitation of Muslim garment workers, as well as how large corporations are taking away from small, Muslim-owned businesses, said Katebi, who organizes a sewing cooperative for refugee women in Chicago. That includes companies like Haute Hijab and Sukoon Active, which have been making modest clothing and activewear for years.

Increasing Muslim representation is not just an ineffective strategy for fighting Islamophobia, but a dangerous one, Kazi said, as it misunderstands Islamophobia as an individual bias, rather than a structural apparatus.

“The hypervisibility of Muslims is undeniably linked to the political climate,” she said. “So while the public is casting this gaze over Muslims in the U.S., what falls out of the conversation are political histories, regional inequality, the histories of white supremacy and race.”

Muslim women are at the forefront of pushing such issues into mainstream political discourse, particularly in electoral politics and grassroots organizing. Michigan’s Rashida Tlaib and Minnesota’s Ilhan Omar, who next month will become the first Muslim women in Congress, ran on progressive platforms that included a $15 minimum wage, “Medicare for All,” and abolishing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Katebi described her vision for systemic change: those who make art and those who do politics partnering with impacted communities to secure material gains. “Our liberation,” she said, “is not going to come from multibillion-dollar, capitalist corporations headed by white people.”

Freedom and justice, for Muslims and non-Muslims alike, will be won at the polls and on the ground — not in the checkout aisle.