New Straits Times Online

THE deputy prime minister’s recent disclosure that Malaysia is losing its halal edge may come as a shock to Malaysians who still think that the country is one of the leaders in the global marketplace. Headlines such as this — “Malaysia is world pioneer in halal industry”— has lulled people into a false sense of security. We remained confident that we were still in the forefront of the industry. We were oblivious to the fact that other countries had stepped in and made their presence felt. We started before others, but we have “allowed others to catch up” and “some have even taken over the vital role we played”, he had said.

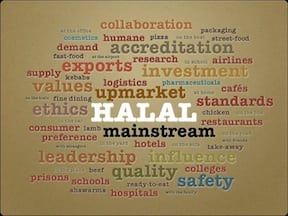

The absence of a consistent plan of action to continue the halal project to its completion is responsible for the industry’s current predicament. Hopefully, his assessment of the situation will be a wake-up call for those involved in the industry. It is a clear signal underlining the urgency of boosting productivity and innovation in the light of growing global demand for halal products and services. The current global market value for trade in halal food and non-food products is around US$2.3 trillion (RM9.68 trillion) annually. Malaysia exported local halal products worth RM42 billion last year from RM38 billion in 2014. The global Muslim population is expected to reach about 2.2 billion in 2030 and the need for halal products is likely to rise progressively. This has stimulated the development of halal products and services and, at the same time, influenced the con sumption habits of non-Muslims in Thailand, Singapore, Japan and Australia, among others.

However, most of the producers of halal products in Malaysia are small- and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs) which lack the capacity to meet the demand of the global halal market. It seems logical that big corporations and SMEs join forces to create strategic collaborations to respond to the global call for halal products and services, and in the process, transform Malaysia into a top player. This should be the priority of the new follow-through action plan for the industry.

Malaysia does have key strengths. The well-placed halal industry’s business ecosystem provides a catalyst for growth. The government and private sectors also seem keen to work closely through programmes which include knowledge sharing, funding and training. Malaysia has 21 Halal Parks, of which 13 are endorsed by the HALMAS certification. HALMAS is accorded to Halal Park operators who have successfully complied with the requirements and guidelines stipulated under the Halal Industry Development Corporation’s designated Halal Park.

Malaysia’s Jakim-driven halal certification is well-accepted internationally and the Malays

ian Islamic Development Department has begun exporting its knowledge and expertise to countries that are setting up their own halal-certification process. It’s vital for Malaysia to build on that foundation. Moving ahead, as the deputy prime minister puts it, is to “work as one”. That means encouraging all relevant players to come together “to take the industry forward”. Malaysian businesses (big and small) must step up their game on innovation, not just for their own success but for the economic and social well-being of communities, regions and the country.

ian Islamic Development Department has begun exporting its knowledge and expertise to countries that are setting up their own halal-certification process. It’s vital for Malaysia to build on that foundation. Moving ahead, as the deputy prime minister puts it, is to “work as one”. That means encouraging all relevant players to come together “to take the industry forward”. Malaysian businesses (big and small) must step up their game on innovation, not just for their own success but for the economic and social well-being of communities, regions and the country.

ian Islamic Development Department has begun exporting its knowledge and expertise to countries that are setting up their own halal-certification process. It’s vital for Malaysia to build on that foundation. Moving ahead, as the deputy prime minister puts it, is to “work as one”. That means encouraging all relevant players to come together “to take the industry forward”. Malaysian businesses (big and small) must step up their game on innovation, not just for their own success but for the economic and social well-being of communities, regions and the country.

ian Islamic Development Department has begun exporting its knowledge and expertise to countries that are setting up their own halal-certification process. It’s vital for Malaysia to build on that foundation. Moving ahead, as the deputy prime minister puts it, is to “work as one”. That means encouraging all relevant players to come together “to take the industry forward”. Malaysian businesses (big and small) must step up their game on innovation, not just for their own success but for the economic and social well-being of communities, regions and the country.