By Abdalhamid Evans, Senior Strategist, Imarat Consultants UK – Founder, HalalFocus

Like a picture on an inflating balloon, the shortcomings within the Halal industry are getting bigger as the market expands.

Like a picture on an inflating balloon, the shortcomings within the Halal industry are getting bigger as the market expands.

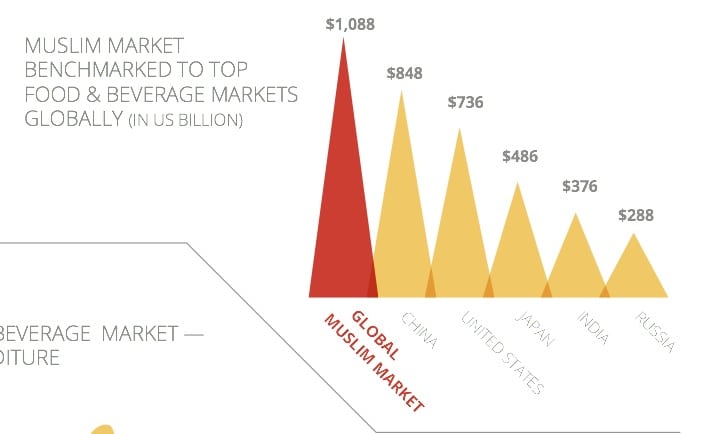

There is no doubt that it is expanding. The DinarStandard-Thomson Reuters Report on The State of the Global Islamic Economy 2013 valued the Halal Food and Beverage market at just under $1.1 trillion. The same report expects the market to be worth $1.626 trillion in 2018.

There is a core customer base of 1.65 billion Muslims scattered across the globe, a population that is growing at twice the rate of the global average. 61% of this growing population is under the age of 30. This is an underserved and under-recognised market that is now –finally– getting the attention of governments, MNC’s, entrepreneurs and investors across the world. Not to mention an increasingly aware and vocal consumer base who now have access to an unprecedented level of information on the subject.

The foundation of this market is in compliance with Halal parameters. The self-appointed guardians of this compliance are the Certification Bodies, most of which fall into two categories: Government linked authorities and private sector businesses.

The government linked bodies, such as JAKIM in Malaysia, MUIS in Singapore, MUI in Indonesia have a monopoly on the audit process and the issuance of certificates. They are not monitored by any higher authority, and are naturally prone to the usual levels of inefficiency and potential for corruption that characterises any government agency anywhere.

The private sector CB’s that operate in the non-Muslim food exporting countries are self-appointed entrepreneurial Muslim businesses and mosque linked organisations who have recognised the significant profits that can be derived from the Halal certification business.

These private sector CB’s claim that all Halal food producers needs to be certified by them in order to demonstrate to their customers that their products are indeed Halal. They do not approve of food producers that self-certify. They engage in tactical battles with their competitors, usually by trumpeting their own adherence to the Shariah and Sunnah of Islam, and by pointing out the shortcomings and deviations of their competitors.

The problem with both these groups of CB’s (with the possible exception of Australia and New Zealand) is that they themselves are all self certified. They conduct the audits, issue the certificates and send their invoices all without any outside supervision by any form of accreditation body. The Halal marketplace is riddled with stories of bullying tactics and conflicts of interest

This scenario is at odds with the accepted norms of the mainstream food and beverage industry. Compliance to HACCP, GMP, GHP, BRC standards is normally done via third-party audits; ie the audit process is separated from the issuance of the certificate of compliance, and the auditors themselves are required to be an accredited body, recognised by the likes of UKAS in the UK and ANSI in the USA. The certifiers themselves are certified, and it is visible by the double logos, one for the auditor, and another for the accreditation body that can be seen on mainstream food packaging.

Until a similar degree of oversight is practiced in the Halal sector, there will continue to be fraud, infighting and a lack of both consumer and investor confidence in the Halal market space.

This is not necessarily the direct fault of the CB’s. They have emerged out of a need, and have evolved along with the market, and the problems are, for the most part, systemic and structural rather than intentional or devious. What is missing is the kind of leadership from governments and Islamic institutions that can bring the Halal sector practices up to speed with the normative practices of the non-Halal mainstream market.

The Halal standards that have been developed by Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries (SMIIC) and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), currently under the secretariat of the Emirates Standards and Metrology Authority (ESMA) may…against all previous odds…be in a position to bring a solution to this problem.

If (and we will see how big an if this turns out to be) the GCC countries adopt the SMIIC-OIC standards, then the tide will start to change. These standards cover not only food production, but, significantly, the parameters for both Certification Bodies and Accreditation agencies. They lay down a very specific set of guidelines for CB’s, and furthermore, they require the CB’s to be compliant with ISO 17021: Conformity Assessment – Requirements for bodies providing audit and certification of managements systems.

For most independent CB’s operating in the non-Muslim food exporting nations, this may well turn out to be a significant watershed. CB’s around the world will in all probability be required to participate in the scheme that accompanies these standards. It may well be that the bigger multi-national auditing companies, such as Intertek and SGS, will see this as the long-awaited opportunity to gain a stable foothold in a market that has long eluded them…something that would be a real blow to the independent Muslim-led CB’s

Even the JAKIM’s and MUI’s of this world may struggle with ISO compliance…

If these standards do become the passport to entry into the valuable export markets of the GCC ($81 billion in annual F&B expenditure in 2012), then these new parameters will get the attention of all the major food exporting countries and companies in the world.

If these are actually adopted and enforced by the OIC, it will impact the $191 billion spent annually on food imports by the 57 OIC member countries.

Whether this happens remains to be seen. The OIC has in the past not enjoyed a reputation for dynamic action. However, if the OIC-SMIIC-ESMA linkage gets the support of the UAE, spurred on by Dubai’s push to be the capital of the Global Islamic Economy, then the usual dynamics (or lack thereof) may well change. A new kind of horsepower may well kick-in.

With national agendas and national pride on the one hand, and the world’s biggest food companies on the other, it is likely that the rules of the game that have been in operation for the past few decades in the Halal sector may well be about to change.

Whatever the case, for the CB’s, the days of operating without any regulatory oversight may well be coming to an end. Time will tell.

If you want to share this article please include Author’s name.