By Abdalhamid Evans, Founder, HalalFocus.com

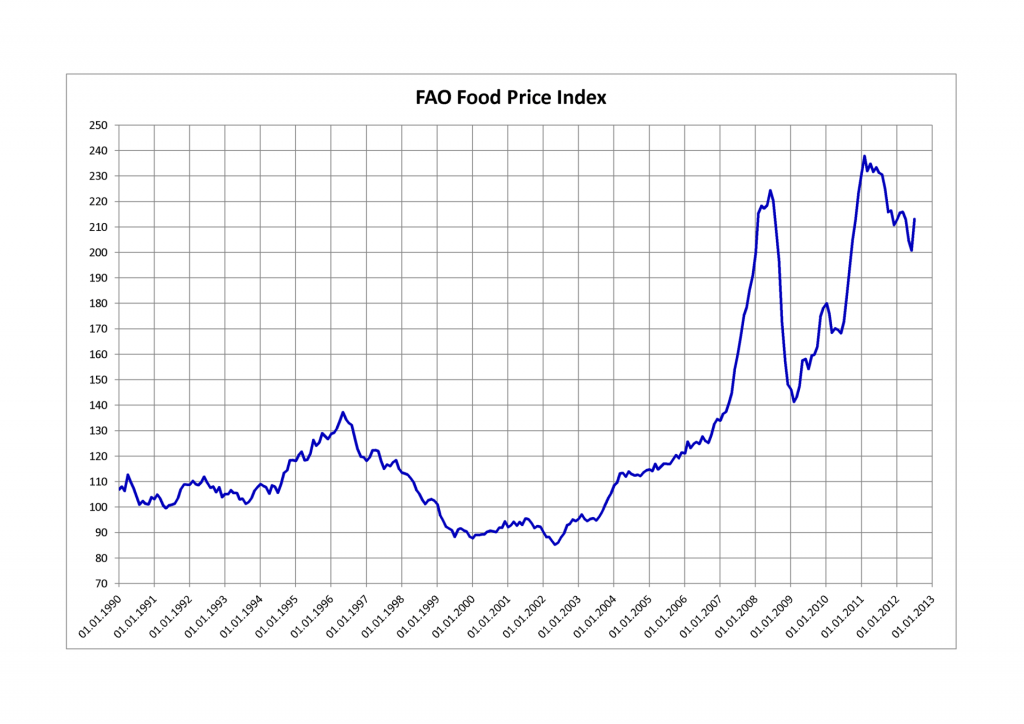

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, its Food Price Index in February 2011 rose for the seventh month in a row to reach 231, topping the peak of 224 last seen in June 2008. It is the highest level the index has reached since records began in 1990.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, its Food Price Index in February 2011 rose for the seventh month in a row to reach 231, topping the peak of 224 last seen in June 2008. It is the highest level the index has reached since records began in 1990.

In 2008, many governments around the world had enough money to fund food subsidies to prevent the price increases trickling down to street level. Now, a couple of years on, most governments do not have the cash to fund subsidies, and the price rises are starting to bite where it hurts, i.e. in the pockets of the people.

In an interview, Laurie Garret, formerly a Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations made an analysis of the current food price crisis that is gripping the world, and in particular the poorest among us. She cited four main reasons for the price rises:

-

Expanding middle classes causing greater demand for meat and dairy products, leading to more grain being used to produce animal feed than to feed people

-

More agricultural land being used for biofuels. We are feeding our cars, and not our people.

-

Speculation in the basic food commodity markets leading to huge artificial price spikes that are good for profiteering, and bad for anyone who actually wants to use these commodities.

-

Severe and unpredictable weather conditions.

The UN’s special rapporteur on the Right To Food, Olivier de Schutter has remarked that what happened in 2007-8 was a “price crisis, not a food crisis”, precipitated by speculation in the financial market that was not linked to insufficient food being produced. He blamed the “inaction to halt speculation on agricultural commodities”

De Schutter is in no doubt that speculators are behind the surging prices. “Prices of wheat, maize and rice have increased very significantly but this is not linked to low stock levels or harvests, but rather to traders reacting to information and speculating on the markets,” he says.

The main culprit is the commodity derivative. Commodities are the actual raw materials while ‘commodities derivatives’ are financial contracts derived from the value of the underlying commodity. At the base of the commodities derivatives bubble is the ‘futures’ contract, which traditionally brought together buyers and sellers in a regulated auction market (like the Chicago Board of Trade in the US), to bid and settle a price for the delivery of a quantity of a commodity at an agreed time and place.

This basic futures contract enabled commodity sellers, such as farmers and grain elevator operators, to avoid sudden price drops and commodity users or traders to avoid sudden price increases; it was generally regarded as a kind of insurance.

But it ceased to work as such after the deregulation of the global agricultural markets.

The consequence of deregulation was to replace local market access for the majority of small farmers with global market access for a few global transnational companies like Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, General Mills or Monsanto.

After the mortgage crisis that tumbled stock markets across the world, investors put their money instead into commodities, and to cash in on the new biofuels boom. Grain traders started withholding supplies in the hope of higher prices, knowing that grain reserves were down, and prices volatile.

At the same time, speculative investors began hedging their bets on grain futures, driving up prices even further. The biofuels boom has exacerbated speculation and high prices, but that boom would not have been possible without a deregulated global market.

Deregulation has brought even bigger players to the derivatives market… the big, unregulated, financial institutions, namely the investment banks –that are not commodity users. These big speculative institutions now dominate the commodities markets much more than the commodity users.

In March 2008, Goldman Sachs (charged for fraud over sales of ‘toxic’ mortgages) and Morgan Stanley owned 1.5 billion bushels of Chicago Board of Trade corn futures contracts, while all the regulated hedgers together owned only 11 million bushels (a ratio of 136:1).

These investment banks operate through commodity index funds that bundle together up to 24 agricultural and non-agricultural commodities in a single investment portfolio that usually bets on prices to go up.

As the component contracts are about to expire (90 days for agricultural futures, six months for non-agricultural commodities) the banks sell the contracts to take profits, creating price volatility in the wake of selling.

Since 2003, commodity index speculation has increased 1,900%, from an estimated $13 billion to $260 billion.

According to Mike Masters, fund manager at Masters Capital Management, “We first became aware of this [food speculation] in 2006. It didn’t seem like a big factor then. But in 2007/8 it really spiked up. When you looked at the flows there was strong evidence. I know a lot of traders and they confirmed what was happening. Most of the business is now speculation – I would say 70-80%.”

Masters who testified to the US Senate in 2008 that speculation was driving up global food prices, says the markets are now heavily distorted by investment banks. “Let’s say news comes about bad crops and rain somewhere. Normally the price would rise about $1 [a bushel], but when you have a 70-80% speculative market, it goes up $2-3 to account for the extra costs. It adds to the volatility. It will end badly as all Wall Street fads do. It’s going to blow up.”

Halal Sector Responsibility

Market speculation in basic food commodities is illegal under Islamic Law. The Shariah parameters that define prohibited transactions are a series of control mechanisms to safeguard the poor, to keep basic food prices always within the reach of all members of the society.

Weather cannot be controlled, and failed crops will always drive up prices, and belts get tightened accordingly. But price speculation in basic foods by financial institutions that do not even take possession of the commodities simply cannot be allowed to continue.

There is talk about Halal market values, and about developing a Halal economy. In order to make any significant steps in this direction, there has to be a move to end these unacceptable speculative practices.

The awful irony is that of the one billion hungry around the world, half are small farmers, a quarter are landless labourers working on plantations and the rest are urban poor who have migrated from rural areas because they can no longer find a living there.

It cannot be acceptable that the poor man’s meal is the rich man’s derivative instrument.

If we are to see any meaningful convergence between the Halal food sector and the Islamic Financial sector, there has to be a voice that emerges from this union to put an end to basic food commodity speculation.

If we are to have Shariah-compliance in the food and finance sectors, it cannot just take the form of a cosmetic and superficial compliance. We have to dig down into the matter until we reach the bedrock core values and put some mechanisms in place to protect the right of the poorest among us to eat and drink.

If the large western exchanges are unable or unwilling to regulate this form of speculation, then surely the Muslim world has the resources and the buying power to create a commodity exchange that is regulated by the Shariah rulings that forbid the practice of getting rich by starving the poor. The question only remains as to whether there is the will to do so.

If the Islamic Financial sector is looking for a way to become a driver in the real economy, it does get much more real than this.

“Eat of the good things We have provided for you, but do not go to excess in it or My anger will be unleashed on you. Anyone who has My anger unleashed on him has plunged to his ruin.” (Qu’ran 20:81)