By Theo MERZ – AFP

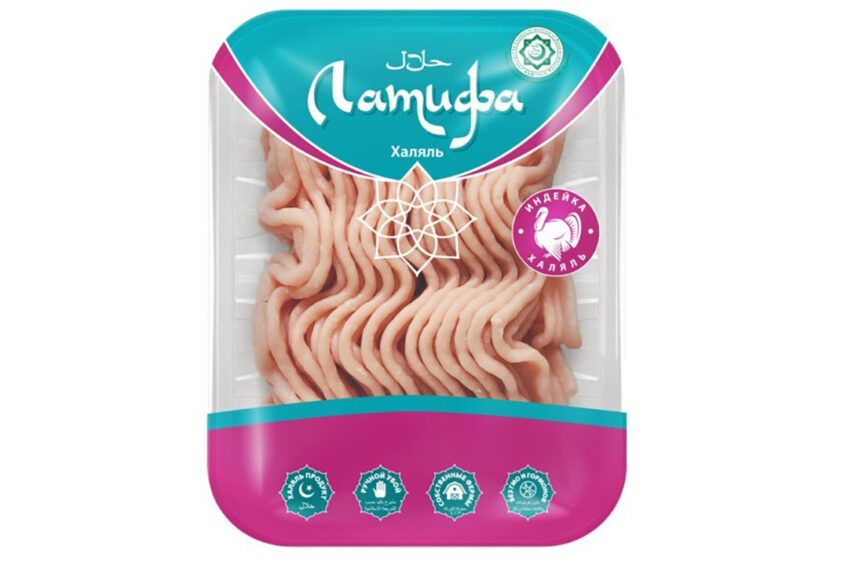

Shchyolkovo (Russia) (AFP) – The manager of a sausage factory near Moscow, Arslan Gizatullin says his halal business has been feeling the pinch — not so much from Russia’s sluggish economy but competitors vying for a piece of a growing Islamic market.

Ever more producers are catering for the domestic Muslim community, which accounts for around 15 percent of Russia’s population and is set to expand, and in some cases are also setting their sights on export.

“In the last few years in general, halal’s become something of a trend in Russia,” said Gizatullin, who has been at the Halal-Ash plant in the city of Shchyolkovo for seven years.

The factory was among the first of its kind when it opened two decades ago, recreating Soviet-style sausages in accordance with Islamic law, among other products.

“Now I go to shop displays and I see sausage from one, two, three producers… I see that competition is growing,” he adds from the factory, which employs 35 people and puts out up to 1.5 tonnes of produce a day.

The halal economy, worth more than $2.1 trillion globally, is far from limited to meat.

Cosmetics firms and services such as halal hotels have received licenses from the body that oversees Islamic production in Russia, while state-owned Sberbank is looking into creating an Islamic finance entity.

The Centre for Halal Standardisation and Certification, under the authority of the Russian Council of Muftis, has approved more than 200 companies since it opened in 2007.

The centre says that number is growing by five to seven companies a year — from a standing start at the collapse of the anti-religious Soviet Union.

Lessons from the Arab world

Rushan Abbyasov, the deputy head of the Council of Muftis, told AFP the Russian agriculture ministry was supporting the centre in its efforts to increase exports to the Arab world and Muslim-majority ex-Soviet republics.

“We’ve looked at international experience in the Arab world, in Malaysia, and we’ve developed our Russian (halal certification) standard following that model,” Abbyasov said in an interview at Moscow’s central mosque.

“We’re doing it in a way that matches international halal standards as well as the laws of the Russian Federation.”

The mufti pointed to an annual exhibition of halal goods and producers in the Muslim-majority Russian republic of Tatarstan, which this year saw its biggest ever turnout, as an example of the sector’s growth.

Tatar officials told Russian media the halal food market accounted for around 7 billion rubles a year ($110 million) — or just over three percent of the region’s gross agricultural output.

But they said the sector was growing at a rate of between 10 and 15 percent a year.

The certification centre said Russia’s overall halal economy was also growing at a rate of 15 percent every year, but declined to give a breakdown of its figures.

Russia’s overall economy is stagnant, with the government predicting growth of only 1.3 percent this year, after 2.3 percent growth in 2018.

More than just business

Alif, a Moscow-based cosmetics firm, is a new company at the forefront of the move towards exporting halal goods from Russia.

Manager Halima Hosman told AFP that, a year after launching, Alif’s products were being sold in the Muslim-majority Russian republics of Dagestan and Chechnya, as well as ex-Soviet Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

“Our priority targets for export now are France, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia,” she said, adding that the company had non-financial support from the halal certification centre.

The 28-year-old, who was born into an Orthodox Christian family in southern Moldova but converted to Islam as a teen, said promoting halal products was about more than business.

“It’s a way for people who don’t know about Islam, who aren’t Muslim, to find out about what ‘halal’ actually means,” Hosman added of the alcohol- and animal fats-free cosmetics.

Lilit Gevorgyan, principal economist for Russia and former Soviet states at IHS Markit, said the growth in Russia’s halal economy seemed impressive but was coming from a “very low base”.

Further growth in the sector was likely to be driven more by export than by domestic demand, she said.

This is mainly because household incomes have yet to recover from a 2014 crisis caused by a fall in global oil prices and Western sanctions over Moscow’s annexation of Crimea.

“Halal food is more expensive due to its production costs, and for Russian consumers… every ruble counts,” she said, adding that much of Russia’s Muslim community was non-practicing.

Changing Muslim countries’ perception of Russia will be key if Moscow is serious about increasing halal exports, Gevorgyan added.

“Branding is important,” she said, adding that Russia — as yet — is not seen as a major halal producer.