Stanley Hainsworth has been a catalyst for the great brands of modern times. He was creative director at Nike and then Lego. He was vice president global creative at Starbucks in an era when the coffee purveyor was experiencing phenomenal growth. Starbucks has been hailed, acknowledged, and praised again and again for its excellence in branding and marketing, in creating a branded experience that can satisfy the connoisseur, bring in new converts, be accessible to all, and irresistible in its appeal. Stanley defined the very feel of Starbucks in an era when the brand was becoming a cultural icon.

Stanley has a reputation for being extremely rigorous in his work, comprehensively rethinking brands when necessary, and helping them to expand into new areas of endeavor while remaining true to their original identity. As he had done at Nike, he helped Lego expand into entertainment properties that allowed the company to gracefully enter the brand multiverse. At Starbucks, he created an innovative criteria of five filters–handcrafted, artistic, sophisticated, human, and enduring–that defined the work for the company. Stanley’s extraordinarily thorough approach to design and branding is complemented by an equally good nature; he has been a revered colleague and mentor at the companies where he worked.

With such an extraordinary range of experience, Stanley has become ever more articulate about how brands work, and he has now devoted himself at Tether to invigorating existing brands and crafting new ones. Having guided brands at companies that have gone through dramatic growth spurts–or needed to move on to a new phase–he has compelling thoughts about how brands stay relevant and authentic as they get older and grow. Many brands have lost their way in the process of evolving from a small company to a much bigger corporation. Finding themselves disoriented, they must reassess. “In order for brands to recapture their spirit, they almost always go back to their core,” he says. Authenticity in branding requires a step by step, measured methodology that doesn’t veer from a brand’s key identity. Certain brands have not been able to articulate that, and Stanley’s comment about Microsoft never having told its story was wonderfully sharp.

In this interview, Stanley reveals his secrets about the magic that helped to create a brand that conquered the world. The sensation that is Starbucks required elements of wisdom, integrity, showmanship, and intelligence. I got the sense talking with Stanley that each of the points he made–about Starbucks and other topics–could be explained in even greater detail. Each could have its own commentary in which Stanley unfolds, like an accordion, the full three-dimensionality of his experience and insight.

Stanley speaks here about the importance of vision. It is a theme that can’t be emphasized enough. Nike had vision. Starbucks had vision. Stanley shares an insider’s view of the Starbucks’s history, and it’s interesting to learn that even Starbucks CEO Howard Scultz didn’t fully realize his company’s potential for growth. But he had a vision, and he, like the leaders of Nike, were relentless in bringing this to fruition and using it to craft the brand experience. Rigor in matching the vision to the brand experience is essential, and that must define every brand touchpoint. As Stanley says, “No one is going to pick up your product and try it if they don’t want to buy into the experience.” The man has vision.

Stanley, how would you define “brand”?

Stanley, how would you define “brand”?

A brand is an entity that engenders an emotional connection with a consumer.

What do you mean by an “emotional connection”?

Consumers emotionally connect with brands when the brands repeatedly provide something that the consumer wants, desires, or needs.

Let’s return to the moment a person first realizes they have to make a choice between coffee brands or soda brands or shampoo brands. How do people really make choices? Do you think people are conscious of the processes they use?

I think the best brands are those that create something for consumers that they don’t even know they need yet. A coffee brand like Starbucks created something people didn’t know they needed. Same with Nike. Who knew we needed a high-end performance running shoe? I think when people are surprised or delighted by how a brand can change their lives by just making it a little bit better–or a little bit more fun or a little more performance-oriented–that’s when they start creating a connection with that brand.

The concept of a person not knowing that they need something is a fascinating one. Clearly, there were millions of coffee shops all over the world before Starbucks launched its particular brand of coffee shop. How do marketers create desire for something that consumers don’t know they need?

I think great brands create the “end state” first. When launching a new product, marketers are not very specific about how a product actually works. They express more about the result. They talk about what you will feel or what you will be like if you choose to engage with that brand or that product. The Apple commercial in 1984 was a great example of this. There was very little about the product in the spot. It was all about the aftereffect of the product.

During your tenure at Starbucks, how deliberate were the choices that the Starbucks marketing team was making? Were they very intentionally creating a scenario and an environment that people would want to experience?

I think it was very deliberate from the beginning. When Howard Schultz first came to Starbucks, he wasn’t the owner of the company. He joined a couple guys that had started the company. He went over to Milan and saw the coffee culture and espresso bars where people met in the morning. He saw how people caught up on the news while they sat or stood and drank their little cups of espresso. That inspired the vision he crafted from the beginning–to design a social environment where people not only came for great coffee, but also to connect to a certain culture.

Howard was very wise in knowing that Starbucks was not the only company in the world to make great coffee. On the contrary, there are hundreds of other companies that can make great coffee. So what’s the great differentiator? The answer is the distinction that most great brands create. There are other companies that make great running shoes or great toys or great detergent or soap, but what is the real differentiator that people keep coming back for? For Starbucks, it was creating a community, a “third place.” It was a very conscious attribute of the brand all along and impacted every decision about the experience: who the furniture was chosen for, what artwork would be on the walls, what music was going to be played, and how it would be played.

Did Howard anticipate that Starbucks would grow as quickly as it did and become as pervasive? Was his goal to create a global brand?

I think the vision was always for Starbucks to become a global brand. There were big ambitions from the beginning. I once asked Howard how it felt to have thousands of people here in our offices, and thousands of people in thousands of stores all over the world working for the brand. He just looked at me and shook his head and said, “I had no idea that it could become this.”

Over the course of your career, you’ve worked in three different companies that have an iconic role in our culture. With two of them, Starbucks and Nike, the products are sold at a very high premium. Both organizations have taken commodity products and turned them into desirable, sexy, coveted products that incite enormous loyalty and an almost zealotlike behavior. Do you see a common denominator in the way these products are marketed? Would you say that there’s something that these companies have in common that has generated this fervor?

What I observed working in both companies is the rigor and unfailing attention to the product, and the unbelievable energy spent on creating the brand experience. I describe it as experience first and product second, because no one is going to pick up your product and try it if they don’t want to buy into the experience. This experience comes through the advertising, the retail environment, and the online experience–every single brand touchpoint. There is a very intentional effort to inspire people to get caught up in that experience and say, “I want to try that”–whatever that thing happens to be.

What is the most important aspect to consider when creating a brand?

For me, it’s all about having a story to tell. This is what will enable you to create an experience around the brand.

What do you mean by “a story”?

Every brand has a story, whether it’s the founder’s story or the brand’s reason for being. Some brands have never told their story well, or have lost their story. Microsoft is a good example of a brand that’s never told its story well. It’s a huge consumer product software platform, a mega conglomerate, and there’s no love there. There’s no emotional story to rally around. The Bill Gates story is such an incredible story, but it’s never really been expressed by the brand.

It’s really interesting to watch brands get older, and gain more competitors in the marketplace, and struggle to stay relevant. Look at Levi’s or Gap or any of the great American brands that have gone through these struggles. Look at Starbucks! In order for brands to recapture their spirit, they almost always go back to their core. They seem to forget for a while, then remember, “Oh yeah, we’re a coffee company!” Then they get rid of the movies and the spinning racks filled with CDs and start focusing on coffee again.

What if the brand manager of Kraft American cheese asked you to develop its story? How do you create a story if something is essentially manufactured?

You go back to the essence of the brand. Why was it made? What need did it fill? Go back to the origins of a brand and identify how it connected to consumers and how it became a relevant, “loved by families” product. What were the origins of this story? Whether we’re talking about Tropicana orange juice or Kraft American cheese — these products were all created to fill a niche. Why? That’s where you’ll find your story.

What would likely be the next step after defining or developing a story?

You develop a story, and then you start to identify who the consumers are. Who are you talking to? How are you going to talk to them? How are you going to tell your story to them? What are your opportunities or your channels through which you can tell that story? Do we need to design some new products, or do we need to redesign our existing products because they aren’t true to our story? Or maybe you determine that your products are fine, but you haven’t been talking to your consumers in the right way, so it’s a communication issue. Examine every touchpoint and look at how you can tell one clear, consistent story.

People who aren’t very experienced with branding, or are new at it, sometimes feel that they can get away with something being off-brand. But I think that genuinely good branding involves an examination of every single way the brand, the product, and the experience is viewed. Everything that you do, everything you release, everything you say — everything is the cumulative expression of your brand.

What made you decide to work with brands in the first place?

As an American, my earliest days were immersed in brands. Brands became my acquaintances and friends as I grew up. When I got old enough to understand what was going on, I couldn’t help but wonder about all that power.

What brands did you have emotional connections to when you were younger?

I think boys always remember their first really nice pair of running shoes. Mine were Adidas. I remember them exactly–I remember what they smelled like, what they looked like. I remember every single detail about them.

What made you want those shoes?

I loved the look of them. I even remember going to buy them. I had earned money mowing lawns. I went to the sporting goods store in Benton, Kentucky, the nearest town that had a sporting goods store–the little town where I grew up didn’t have one. I looked at the shelf, and those were the shoes that called out to me. Even now, when I go into sporting goods stores or shoe stores now and see the huge wall of shoes, I see that one style of shoe — Adidas still makes them — and I have a deep connection to them.

How did you feel when you first put on that first pair of shoes?

I felt like I had joined another world. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had joined the world of consumers. Suddenly, I liked the feeling of earning money, of buying something, and then enjoying it. That started my dangerous journey of buying footwear and apparel over the years.

Did that experience of wearing the shoes — which you had wanted so badly — make you feel better about yourself?

Yes. Yes. Yes.

Why or how do you think that happens?

If the brand has been advertised widely, then you’ve just bought your way into a world that you’ve only seen from the outside. The experience is like when there’s a club that you keep walking by, and you finally enter that club, and now you’re a part of it.

Do you think that there’s any danger in that?

That’s what brands play on. It’s part of our nature to want to be accepted. Yet, at the same time, we have this desire to feel like we’re different from everyone else — which is the complete opposite of that yearning for acceptance but is nonetheless relevant. I found that strategy particularly intriguing — when brands create things that make you feel like you’re different from everyone else.

I remember being in London in the 1970s and first seeing punks in Trafalgar Square. They had their hair “Mohawked” up, and they wore jackets covered in safety pins. I couldn’t help but imagine them at home, preparing themselves to go out, in order to look very different from anyone in their household or in their neighborhood. But once they were out, they looked exactly like everyone else in Trafalgar Square.

No matter how hard we try to look different, we almost always still look like someone. Once a lot of people get access into an exclusive club, the original members get turned off and leave to find another smaller, more exclusive club to join. I have often wondered if I should feel guilty because of my role in this. On the one hand, it is disturbing, but on the other hand, I admire it.

But as much as I believe in this, I also realize that no one has to have those products. You can live without them — they’re not essential to life. I’ve probed deep in my soul to see if I felt bad doing this work, but I never have. I have never felt guilty.

Are you somehow disappointed that you don’t feel guilty?

No. I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s like entertainment. If I write a book or make a movie, I’m going to promote the hell out of it. It’s the same thing in any arena. I make a shoe, and I’m going to promote it and try to get people to buy it. It’s all part of making a living. Some people sell coffee, some people sell bread, some people sell shoes, some people sell toys.

I remember leaving work several years ago, when I was still at Starbucks. I felt so good after a whole day of working with everyone and critiquing everything. At the end of the day I suddenly realized, “Wow, I am really good at this.” I knew I could make emotional connections between consumers and products and brands and things. I’ve achieved a level of expertise in the same way that a doctor or an accountant who practices for many years gets really good at what he does. We practice for years and years and years, and we learn all of the techniques. And then we make up new techniques and new ways to do things. And we get really, really good.

Precisely for that reason, you were brought in by Pepsi to resuscitate Gatorade after a failed brand reinvention. What did you do to resuscitate it?

I borrowed a lot of what I learned from my years at Nike. Gatorade needed a culture of innovation. For the last few years, their only innovation was related to introducing new flavors. That’s not innovation. They needed to start creating products again that showed that they were the leader in both hydration and in sports drinks. I came in and developed a strategy to help them do that. I worked directly with the CEO to design a new identity for the brand, as well as for the products. Then I created the overall brand guidelines. It was a great experience.

What’s it like to start working with a brand when it’s in the middle of a disaster?

You only have one place to go, and that’s up. Are they bringing back the Gatorade name? The G logo is being used in the same way as Nike uses its swoosh. Gatorade is the name of the brand and the company, and the G is the equivalent of the swoosh. The company had gone a bit overboard when it got rid of the Gatorade moniker, and now it’s coming back to help reidentify the brand.

Did you do a lot of market research in the process of working on this project?

Yes, we did a lot of market research. It was interesting coming to this considering my background at Nike, where ideas were validated by gut instinct, not the consumer.

Wow, that’s amazing.

Starbucks was pretty much the same way. As Howard Schultz used to say, “If I went to a group of consumers and asked them if I should sell a $4 cup of coffee, what would they have told me?” Both Starbucks and Nike have modified their position on market research now, and do more of it, but they aren’t like a P&G-type organization where they do heavy-duty qualitative and quantitative market research. When I left Nike, that type of validation was foreign territory for me. I had to learn it all afterwards.

What do you think of the state of branding right now?

I think branding has become a consumer-friendly word. It’s being used in political campaigns, and it’s being used in the boardroom. Schools have even started to talk about branding. On the one hand, there’s a danger the word will become watered down and less meaningful than it has been in the past. On the other hand, it will be fascinating to see how communicators use this opportunity. We have the ability to lead this cultural shift, and I hope we can do it before the term “branding” becomes just another generic, overused, and misunderstood word.

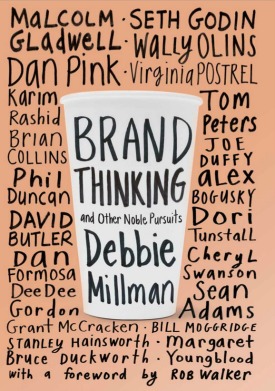

Reprinted with permission from BRAND THINKING by Debbie Millman, Allworth Press.