by Martin Koehring | The Economic Intelligence Unit

Global leaders have set themselves a series of ambitious goals and targets in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Ending hunger by 2030 (SDG 2) or reducing premature mortality from non-communicable diseases by a third (SDG 3), for example, will be no mean feat. Faced with such a plethora of commitments, policymakers should look to fixing global food systems as a treasure trove of opportunity.

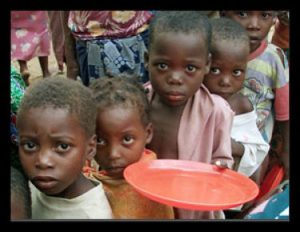

The food waste-hunger paradox

Food loss and waste—primarily developed countries—stands in stark contrast to widespread undernourishment—mainly in developing countries. Around 821m people, or one in every nine, went hungry in 2017. Meanwhile, around a third of the food produced for humans is lost or wasted—about 1.3bn tonnes each year. If only a quarter of the food lost and wasted could be  saved, it would feed 870m people. This is but one example of broken food systems.

saved, it would feed 870m people. This is but one example of broken food systems.

In order to meet SDG 2 (zero hunger) policymakers must look at the economic, social and environmental dimensions of food systems and how they are interconnected. Food loss and waste is one of the three pillars of the Food Sustainability Index (FSI), developed by The Economist Intelligence Unit with the Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition. The other two are sustainable agriculture and nutritional challenges. The FSI shows that France is a global leader in limiting food loss and waste, for example thanks to legislation requiring supermarkets with a footprint of 400 square metres or larger to redistribute leftover food to charities serving poor communities.

Other examples of best practice in reducing food loss and waste identified in the report accompanying the latest FSI results include London-based Winnow’s smart meter technology that, when attached to waste bins, helps chefs to measure, monitor and reduce food waste.

But limiting food loss and waste is not only crucial for SDG 2. It is also an important factor in other SDGs, such as SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) and it is closely associated with other parts of the FSI, notably sustainable agriculture. Agriculture accounts for around 70% of global water use and 30% of greenhouse-gas emissions. A growing world population, increasing urbanisation and deteriorating natural resources means we have to do more with less, while reducing our carbon footprint. This means sustainable agricultural practices also play a major role in SDG 13 (climate action).

The FSI shows that global leaders in sustainable agriculture are Austria, Denmark and Israel. Best practices in sustainable agriculture identified in our study include the deep placement method used by millions of farmers in Bangladesh to reduce fertiliser use and increase yields.

The nutrition challenge

There are many more linkages between the need to fix food systems and meeting the SDGs. For example, addressing the coexistence of overnutrition and malnutrition will be crucial to meeting SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing), as highlighted recently by José Graziano da Silva, director-general of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN.

About 151m children aged under five are stunted, while approximately 38m are overweight. Worldwide, obesity has tripled since 1975. The malnutrition-overnutrition challenge can only be fixed if policymakers revisit how food systems function. This is reflected in some of the best practices that address nutritional challenges, as identified in our study, including compulsory nutrition education within the national curriculum for primary schools, such as in Cote d’Ivoire. Leading countries in the FSI for the nutritional challenges category include Japan, South Korea and Denmark.

Best practices towards the SDGs

SDGs focusing on areas such as hunger, health and climate seem to be the obvious beneficiaries of a shift towards sustainable food systems. But there are important linkages between food systems and perhaps less obvious SDGs too—such as those on poverty (SDG 1), gender equality (SDG 5), and sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11)—thus demonstrating once again that food is a common thread linking all 17 SDGs. The earlier policymakers realise that reforming food systems will provide a powerful lever for sustainable development the closer we get to meeting the SDGs.

Martin Koehring is managing editor and global health lead at the Thought Leadership practice of The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). He is the lead editor of the EIU’s award-winning food sustainability programme.

* Any views expressed in this article are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.