The Guardian Blog

We should be paying more attention to the ‘third one billion’ and the Islamic economic paradigm, argues Jonathan Wilson

The ancient Muslim tradition of commerce along the silk roads and spice trade routes has been rebranded into a phenomenon I have termed “Brand Islam”.

Islamic marketing is a term that is only about five years old. This facelift has seen it flourish into a new marketing sub-discipline, of growing global interest in industry and among scholars. Previously, relevant issues would have been addressed under a banner of multicultural or ethnic marketing; but it’s becoming clear that this approach doesn’t reflect enough of the nuances associated with Muslim consumers and markets. Now, Islamic marketing seems ready to become another must-have in a growing portfolio of marketing degree and professional courses on your CV.

The 2011 Census in the United Kingdom has the Muslim population at 2.7 million, which is 4.8% of the total population. Of those, around 100,000 are converts to Islam, about two thirds of whom are female. There were an estimated 5,200 conversions to Islam in 2011, making it the fastest growing religion in the UK.

In 2010, Miles Young, Global CEO of Ogilvy, described Muslims as the “third one billion” in terms of market opportunity, and bigger news than the Indian and Chinese billions. One quarter of the world’s population are Muslim, with well over half of Muslims today under the age of 25. If we look at Jim O’Neill’s acronyms for the emerging economies to watch – in 2001 it was BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China); and more recently in 2013 MINT (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, Turkey) – then it’s clear that economies with large Muslim populations are growing in importance.

At the end of 2013, at the ninth World Islamic Economic Forum (WIEF), held for the first time outside of the Muslim world, in London, and at the first Global Islamic Economy Summit (GIES), speakers stressed that Muslim majority and minority markets, while rooted in Islamic principles, transcend faith. PwC, Thomson Reuteurs and Dinar Standard used these conferences as platforms to share findings in their new reports. The global expenditure of Muslim consumers on halal food and lifestyle sectors is estimated at $2.3tr (£1.4tr); and Islamic financial assets are growing at 15-20% a year.

We’ve moved beyond Theodore Levitt’s 1983 Harvard Business Review classic on globalisation. Globalisation has not made us all the same – we are seeing evidence of duality rather than singularity. On one level there is a convergence, but we are also becoming more cultural as a mechanism of coping and maintaining a unique identity. This is more about having a cultural compass than a moral compass. An Islamic identity has risen as something that homogenises diverse audiences and governs key behavioural traits. Furthermore, as with other niche segments, there is evidence to show that there are patterns of higher consumption and greater loyalty, when aligned with Islam.

Just as the Chinese have brought us new terms and concepts such as guanxi (social relations) and mianzi (maintaining one’s face); and likewise the Japanese with kaizen (improvement and change for the best) and kanban (just-in-time production); the modern Muslim world has specific characteristics.

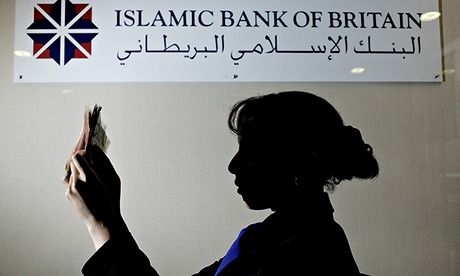

While Sharia finance has been in pole position and halal has been the powerhouse driving the concept of an Islamic economic paradigm, this is about more than meat and money. Brand Islam is joining sectors together, including fashion, cosmetics, entertainment, tourism, education, pharma, professional services and others under one narrative.

We are seeing Muslims searching for a way to reach out and harness spirituality in a post 9/11 era. This is perhaps analogous to a post African-American civil rights movement, where ‘black’ music, comedy, fashion, cosmetics, and sports now transcend race and ethnicity – minority is a mainstream cultural phenomenon.

Author John Grant draws parallels with the Muslim world (which he calls the Interland) and the rise of Japanese brands, like Sony – which manifested a desire to change negative world perceptions towards Japan post occupation in 1945.

An emerging contribution of Islamic marketing is the idea that professionalism cannot be judged by products and services alone. Islam exacts that individuals, in both their professional and private lives, stand beside their offerings and audiences – you practise what you preach. This is not unique to Islam or Muslims, but they are at the forefront of this wider agenda. Furthermore, having made all of these points, relatively speaking there is a paucity of data on what makes Muslims tick and how we should be advertising to them in a way that resonates.

Dr Jonathan A.J. Wilson is senior lecturer in advertising and marketing communications, University of Greenwich