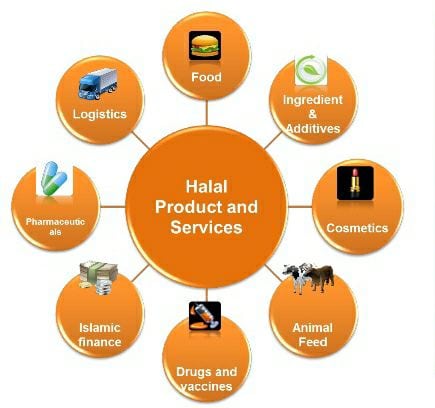

The halal industry — encompassing food, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, logistics/distribution and tourism — is US$2.6 trillion (RM8.33 trillion), almost twice the size of US$1.3 trillion Islamic finance. But, it gets the respect, recognition and reverence of a lunch meeting comprising of “halal kebabs” by Islamic bankers.

The halal industry — encompassing food, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, logistics/distribution and tourism — is US$2.6 trillion (RM8.33 trillion), almost twice the size of US$1.3 trillion Islamic finance. But, it gets the respect, recognition and reverence of a lunch meeting comprising of “halal kebabs” by Islamic bankers.

Let us put the halal text (facts) into the permissibility context (niche market). It is a demand-based consumer non-cyclical, and less volatile than real estate, a favourite of Islamic finance.

It has greater reach and penetration, present in all Group of 20 countries, than Islamic finance, and leading entry into non-Muslim emerging/frontier and developed markets like Vietnam, South Korea, Australia, the US, UK, France and Germany.

It is an indicator of Muslim purchasing power and increasing presence, especially in non-Muslim countries, like the UK, where there are now aisles of halal foods and a store within store, ie, National Halal meats in selected Tesco outlets. Although, there are five Financial Services Act (FSA) approved Islamic banks in the UK, the only deposit taking bank, Islamic Bank of Britain, has encountered financial challenges since its launch in 2004.

It is a national security concern, as part of food security, in all 57 Muslim countries, where food, agriculture, and land bank funds have been launched, and dedicated companies, like Hassad Foods in Qatar, have been established by sovereign wealth funds.

It, food supply chain, is not controlled/owned by Muslims, unlike Islamic finance, hence, concerns of rising integrity risks, where pork DNA is appearing in foods in Europe. For example, it is estimated 85% of the halal food supply is produced by non-Muslim owned companies.

It is about 100% purity, where traces of pork makes the food consumption prohibited, unlike Islamic finance, where “minor” amounts of impermissible revenue/interest, needing purification, still validates the transaction.

It is focused on the certification process for halal compliance, much like Islamic finance focus on standardisation of Shariah-compliance, yet, harmonisation is still work in progress for both.

It does not have global industry body for information intermediation, unlike Islamic finance with accounting/auditing, prudential regulations and capital requirements, and liquidity and hedging documentation contracts.

It is now an asset class, as the socially acceptable market investments (SAMI) Halal Food Index, launched in 2001 by former Prime Minister Tun Ab- dullah Ahmad Badawi, yet halal equity funds, exchange trade funds, private equity funds have not been launched successfully.

The SAMI halal food index has about 95 companies from Malaysia, yet, Bursa Malaysia has not created a halal economic sector index.

Acid Test

One way to determine the importance of any existing product offering is to ask the following hypothetical question:

If halal products were no longer available, what alternatives would the Muslims have? Would they become vegetarians? Possibly.

Would they convert? Unlikely.

Would they eat kosher? Most likely, as many Muslims in the US, including myself, consume Kosher when halal is not available. It is reported that US Muslims consume more kosher products than US Jews.

Now, if Islamic finance is no longer available in, say, Malaysia, global hub for Islamic finance and bell-weather for the industry, what alternatives would the Muslims (and non-Muslims) have?

Would they turn to cash-based economy? Yes, for some transactions, but would be inefficient and disintermediation to the interest-based economy.

Would they turn to ethical finance? Yes, but the preconditions of interest, speculation, uncertainty, and permissibility of underlying asset must still be met for investing, financing and insuring.

For example, on the investing side, the negative screening of Islamic screening, following Securities Commission Malaysia, is aligned to negative screen as- sociated with ethical investing, but Islamic looks at the three financial ratios, where as ethical does not. Thus, ethical investing is not a practical alternative to Islamic investing.

Going forward, I will examine the issues, challenges, convergence, and way forward for the halal industry as part of Muslim consumerism, a subset for an Islamic economy.

Rushdi Siddiqui, a former global director at Dow Jones Indexes and global head at Thomson Reuters in Islamic finance, is now president/ ED of a (halal) US-based agro-food company. He writes this ‘Halal Corner’ column in the Malaysian Reserve.